All of us know these V-shaped streets right in the heart of Nottingham City center…but how much do we know about it ?

FROM ROOKERIES TO PUBLIC REALM : THE STORY OF KING STREET AND QUEEN STREET

🏚️ THE ROOKERIES : A FORGOTTEN NOTTINGHAM

Before King Street and Queen Street became prominent thoroughfares in Nottingham’s city centre, the area they now occupy was once known for something far less distinguished: the Rookeries. In the 18th and 19th centuries, this area between the Old Market Square and what is now the Theatre Royal was a warren of slum housing, narrow alleys, and unsanitary courtyards.

As described in Nottinghamshire History (1907), the Rookeries were “a tangled maze of hovels, courts and alleyways,” notorious for poverty, overcrowding, and crime. These back-to-back houses were built without proper drainage or ventilation. Streets like Chapel Court and Turner’s Yard were emblematic of urban neglect—a stark contrast to the grandeur of the nearby Council House.

Despite its proximity to Nottingham’s civic centre, this part of town was considered a blot on the city’s landscape. Residents lived in dilapidated buildings with leaking roofs, poor sanitation, and no access to light or air—conditions that were sadly common before the advent of Victorian public health reforms.

🏛️ VICTORIAN RENEWAL : KING AND QUEEN STREETS ARE BORN

In the late 19th century, Nottingham embarked on a bold programme of urban renewal. Recognising the need to improve housing, public health, and city aesthetics, the Corporation undertook the clearance of the Rookeries in the 1880s.

What followed was a transformation. King Street and Queen Street were created as formal, wide, and well-laid-out streets cutting through the former slums. This not only improved access and circulation through the city centre but symbolised Nottingham’s aspiration to become a modern, civic-minded city.

Queen Street was aligned to rise gently uphill from the Market Square, and King Street formed a complementary axis. Grand Victorian buildings sprang up, giving the streets a dignified, almost ceremonial quality.

📸 ARCHITECTURAL HIGHLIGHTS : A GALLERY OF NOTTINGHAM’S HERITAGE

The elegance of King and Queen Street is not just in their planning—it’s in the extraordinary architecture that lines them. These streets offer a rich visual history of Nottingham’s golden era, filled with buildings by some of the most distinguished architects of the Victorian and Edwardian periods.

Prudential Assurance Building

Designed by Alfred Waterhouse, one of Britain’s most celebrated architects (also behind the Natural History Museum in London), this Grade II listed building was completed in the 1880s. Its Flemish Gothic façade, complete with red terracotta detailing, pointed arches, and a turreted spire, is one of the most distinctive on King Street. It served as the Nottingham headquarters for the Prudential Assurance Company and reflects Waterhouse’s ability to combine grandeur with functionality.

Prudential Assurance Building, Nottingham, 2025 (free to use)

The Elite Building

This striking Art Deco building, with its strong vertical lines and geometric detailing, was once home to the Elite Picture Theatre—one of Nottingham’s earliest luxury cinemas, opened in 1921. Today, it remains a standout feature of King Street and Queen Street and is used for retail and commercial purposes, still drawing the eye with its elegant façade.

Elite Building, Nottingham, 2025 (free to use)

Fothergill’s Buildings

Architect Watson Fothergill, known for his fantastical and richly decorated style, contributed several buildings near the top end of King Street. These include Gothic Revival commercial blocks with ornate brickwork, turrets, polychrome decoration, and carved stonework. His influence gives the upper parts of the street an almost fairy-tale quality—fusing Victorian whimsy with Gothic precision.

Fothergill’s building, Nottingham, 2025 (free to use)

The Old Central Post Office (Queen Street)

Opened in 1898, the Old Central Post Office on Queen Street is a fine example of late Victorian civic architecture. Designed by Henry Tanner, the building features a grand Baroque Revival façade with Portland stone, pilasters, and a richly decorated arched entrance. Its symmetry and ornamentation speak to the importance placed on public institutions during this period, when post offices were symbols of national connectivity and civic pride. The building remained in use as a post office until the late 20th century and is now repurposed for retail use, but the original detailing—including royal crests and the classical proportions—remains intact. It stands as a proud monument to Nottingham’s development as a modern administrative and communication hub at the turn of the 20th century.

Old Central Post Office, Nottingham, 2025 (free to use)

Jessop & son and John Lewis : A commercial legacy

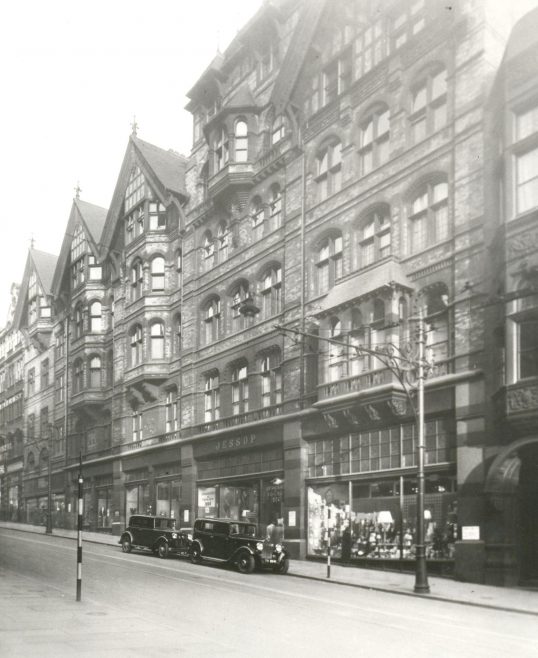

For much of the 20th century, King Street and Queen Street were synonymous with department store culture, and Jessop & Son was one of the city’s most prestigious establishments.

Founded in the 19th century, Jessop & Son began as a drapery and tailoring business and quickly expanded into a full-line department store, renowned for its service and style. The store was located on the corner of King Street and Queen Street, forming a key retail anchor in the heart of Nottingham.

In 1933, John Lewis acquired Jessop & Son, making it one of the earliest regional acquisitions by the now-famous employee-owned retailer. Though it continued trading under the Jessop name for several decades, the store was eventually rebranded simply as John Lewis. For generations of Nottingham residents, this building was a hub of fashion, homewares, and festive window displays, creating cherished memories and symbolising the vibrant commercial life of the city centre.

Jessops at the time of acquisition in 1933, from John Lewis & Partners website

The store eventually relocated to the Victoria Centre in the 1970s, as part of broader commercial shifts. However, the former Jessop’s building still stands and remains a key architectural and historical landmark on the street, a testament to Nottingham’s evolution as a retail destination.

The Brian Clough statue : a civic symbol

Where King Street meets the Old Market Square, one of Nottingham’s most beloved landmarks now stands: the Brian Clough statue. Unveiled in 2008, it honours the legendary football manager who brought Nottingham Forest European glory in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Brian Clough Statue, Nottingham, 2025 (free to use)

Placed intentionally in this spot, a junction of civic life, commerce, and culture, the statue has become a focal point for fans, tourists, and locals alike. Its location underscores the symbolic power of public space and the enduring affection Nottingham has for its heroes.

🚶♂️ A CITY REIMAGINED : THE PEDESTRIANISATION OF OLD MARKET SQUARE

In 2007, Nottingham made another historic leap forward by completely redesigning and pedestrianising the Old Market Square, the largest such space in the UK. This redevelopment removed traffic from the central square and introduced wide, paved walkways, fountains, seating areas, and open space for events and public life.

Old Market Square, Nottingham, 1989. Credit: Peter Mann

As part of this transformation, the lower sections of King Street and Queen Street were pedestrianised or restricted to limited traffic (mostly buses), aligning with modern urban values: clean air, walkability, beauty, and accessibility. These changes allowed the area to flourish with festivals, markets, outdoor dining, and safe pedestrian movement.

King Street and Queen Street, Nottingham, 1980s – Credit : Kieron Dudley

🕰️ CONCLUSION : HONOUR THE PAST, EMBRACE THE FUTURE

Nottingham has spent over a century transforming this part of the city—from the dark, congested alleys of the Rookeries to a pedestrian-friendly urban core. Each generation has added something positive: healthier streets, grand architecture, a thriving retail scene, and inclusive public spaces. Let’s be the next generation to build on that legacy and shape a city centre that’s greener, safer, and more people-friendly.”

It would be a mistake to undo these efforts by reverting King Street and Queen Street to vehicles-dominated corridors. Instead, we should complete the journey: to fully pedestrianise both streets, building on their unique history and existing infrastructure.The architecture demands it. The public realm deserves it. And the people of Nottingham—past, present, and future—expect it.